Park Lane Goods Station holds a unique place not just in Liverpool’s history, but in world railway history. Opened in 1830, it was the world’s first dedicated railway goods terminal, built as part of the pioneering Liverpool and Manchester Railway. While the Liverpool Road station in Manchester handled both passengers and goods, Park Lane was conceived specifically for the movement of freight between the railway and Liverpool’s docks, which even in the early 19th century were among the busiest in the world.

Park Lane was located just south of the city centre, near the waterfront, strategically placed to link ship and rail cargo as efficiently as possible. The station was connected to the Liverpool and Manchester Railway via the famous Wapping Tunnel, itself a marvel of early railway engineering. Running just over a mile in length, the Wapping Tunnel was the first railway tunnel driven under a major city. At the time of its construction, it was considered a tremendous engineering achievement and was seen as essential for Liverpool’s status as a commercial port.

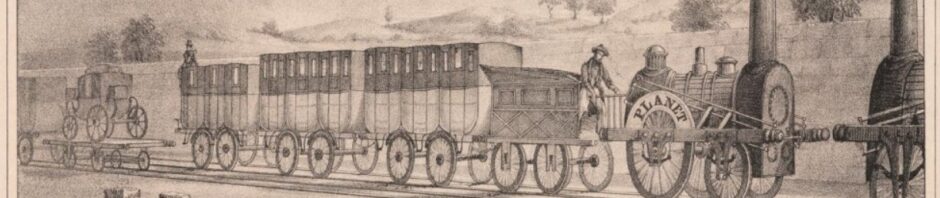

How Park Lane Goods Station would have looked in 1831

The station complex at Park Lane consisted of a large goods yard with multiple sidings, warehouses, loading docks, and hydraulic cranes. It was designed to handle all kinds of freight, from cotton and grain to machinery and livestock. Goods arriving by ship could be transferred directly onto railway wagons for transport inland, while products from Manchester’s factories could be shipped out to the rest of the world via Liverpool’s docks.

One notable technical feature of the station was the use of inclined planes. The Wapping Tunnel ran downhill from Edge Hill to Park Lane with a gradient of 1 in 48 — extremely steep for early railways. Loaded wagons descending the tunnel were controlled by braking systems, while empty wagons ascending back to Edge Hill were originally hauled by stationary steam engines using endless rope systems. Locomotives were not initially used inside the tunnel itself due to concerns about smoke accumulation and ventilation issues.

The incline and rope-haulage system lasted until 1855, when improvements in locomotive power and tunnel ventilation allowed trains to be worked through the tunnel directly under their own steam. Even so, the descent and ascent of the Wapping Tunnel remained a challenging part of operations well into the 20th century.

Over time, Park Lane grew and evolved. Additional sidings and facilities were added during the 19th century to cope with the massive increase in goods traffic. Liverpool’s rise as a global trade centre during the Victorian era meant that the station operated near full capacity for decades. The station was also connected to the wider network of docks via tramways and light rail spurs, creating an integrated system that could move goods with remarkable speed for the era.

However, the station’s location also made it vulnerable during the Second World War. Liverpool was a major target for German bombers, and Park Lane suffered heavily during the Liverpool Blitz of 1940–41. Parts of the goods station and the Wapping Tunnel approaches were damaged, although services continued as much as possible given the wartime importance of maintaining supplies and trade routes.

After the war, Park Lane continued in operation, but changing patterns of goods transport began to erode its importance. The rise of road haulage, containerisation, and the gradual decline of Liverpool’s docks meant that rail freight entering and leaving the city centre became less and less viable. Park Lane saw steadily decreasing traffic through the 1950s and 1960s.

By the early 1970s, Park Lane had become something of a relic. Goods services were increasingly transferred to more modern facilities on the outskirts of the city or handled by lorries. In 1972, the station was officially closed, bringing to an end more than 140 years of continuous operation. The Wapping Tunnel, too, was closed off, though it remained structurally intact.

Today, very little of Park Lane Goods Station survives. The area has been heavily redeveloped, and the site of the old station is now occupied by housing and commercial developments. However, some remnants of the infrastructure still exist. The entrance to the Wapping Tunnel is still visible at the bottom of Park Lane, its imposing brick portal a silent reminder of Liverpool’s early railway heritage.

The Wapping Tunnel itself, despite being out of use, remains a subject of fascination. Various proposals over the years have suggested reopening it for modern rail services or for use as part of a tram or metro system, but none have come to fruition. Urban explorers have entered the tunnel on occasion (illegally and very dangerously), reporting that much of it remains in surprisingly good condition, with original brickwork and features intact.

A technical note of interest: the tunnel was built with a horseshoe-shaped profile, measuring approximately 14 feet high and 14 feet wide — dimensions that were sufficient for the wagons of the day but would be considered tight by modern rail standards. The tunnel was lined with millions of hand-made bricks, an incredible feat of manual labour in an age before mechanical excavation.

Another piece of trivia: in the early days of operation, Park Lane Goods Station was known for its “gravity shunting” — wagons were allowed to roll under control down the slight gradient in the yard to be positioned for unloading, saving the need for locomotives to perform complex shunting manoeuvres.

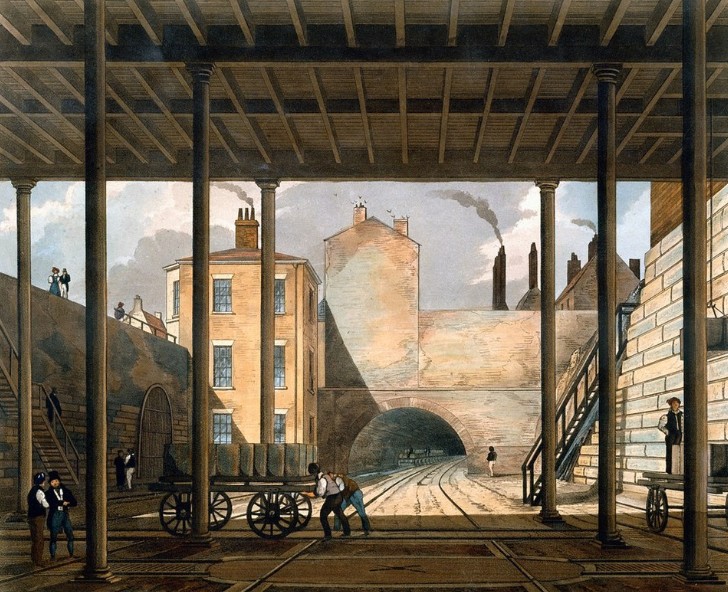

All that is left of the station today, the only hint it was ever there. Thanks to John Bradley, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Park Lane Goods Station is largely forgotten by the general public today, but its importance to the early history of railways cannot be overstated. It proved the concept of a fully integrated rail freight system, paving the way for the goods yards, distribution centres, and container terminals that would follow in the modern era. Even in its absence, it stands as a monument to Liverpool’s pioneering role in the development of railway infrastructure worldwide.