Today I want to talk about one of my favourite things ever: the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Not just because it was the first proper railway between two cities, but because it genuinely changed the world, and it all started right here, practically on my doorstep.

I’ll try not to waffle too much, but fair warning — when it comes to trains, I always waffle.

So. Let’s get into it.

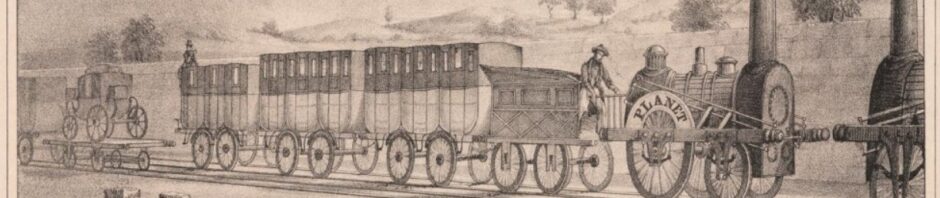

Lithograph of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway crossing the Bridgewater Canal. The artist was A. B. Clayton

Back in the early 1800s, Liverpool and Manchester were booming. Liverpool was already a world-famous port, unloading ships packed with cotton, sugar, tobacco, and other goods. Manchester was fast becoming the textile capital of the world — “Cottonopolis,” they called it.

But getting stuff between the two cities was a nightmare. Roads were muddy messes and it took days for carts to trudge 35 miles. The canals helped (especially the Bridgewater Canal) but they were overcrowded, slow, and expensive. Something had to give.

Cue the idea of a railway. Steam engines were a new and controversial thing. People used small railways in mines, pulled by horses, but a steam-powered railway for long-distance freight and passengers? Madness! Dangerous! Terrifying! At least, that’s what a lot of people thought.

Around 1822, a few brave souls decided to make it happen. A Liverpool corn merchant called Joseph Sandars, and an engineer called George Stephenson, were two of the main characters. There were lots of arguments. The canal owners obviously hated the idea. Landowners didn’t want dirty steam monsters near their fancy houses. Parliament had to be convinced, and the first attempt to get permission failed. (Stephenson didn’t help himself by doing a dodgy survey without properly getting onto the land.)

Eventually, after a lot of arguing and a better survey done by other engineers, they got the Act of Parliament in 1826. They could officially build the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

It wasn’t an easy build. One of the biggest nightmares was Chat Moss — a giant floating bog halfway along the route. Everyone thought it was impossible to cross, but George Stephenson came up with a crazy plan to “float” the tracks on bundles of brushwood and earth. Somehow, it worked. (And incredibly, it still works today.)

They had to dig massive cuttings through rock, like at Olive Mount. They built the Wapping Tunnel under Liverpool, the first tunnel under a city for trains. And everything was done by hand, with picks, shovels, black powder, and back-breaking labour.

At first, they weren’t even sure if they should use moving locomotives or just put stationary engines and pull the trains on cables. So they held a competition — the Rainhill Trials, in 1829.

That’s where George Stephenson’s Rocket came in. It blew everyone else away. The Rocket was fast, light, powerful, and reliable. It changed locomotive design forever. The others mostly broke down or exploded. (You can still see the Rocket today at the Science Museum if you’re ever down in London.)

Finally, the railway opened on the 15th of September, 1830. It was a huge event. The Duke of Wellington, who was Prime Minister, came along. Sadly, the day is also remembered for tragedy: William Huskisson, Liverpool MP and railway supporter, was killed by the Rocket at Parkside Station after trying to cross the tracks at the wrong time. It was the first high-profile railway fatality.

Despite the accident, the railway was a roaring success almost straight away. Trains could get between Liverpool and Manchester in about two hours — sometimes faster — instead of taking days. People loved it. Goods moved faster. Industry exploded. And very quickly, railways started popping up all over Britain and then the world.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway introduced so many firsts:

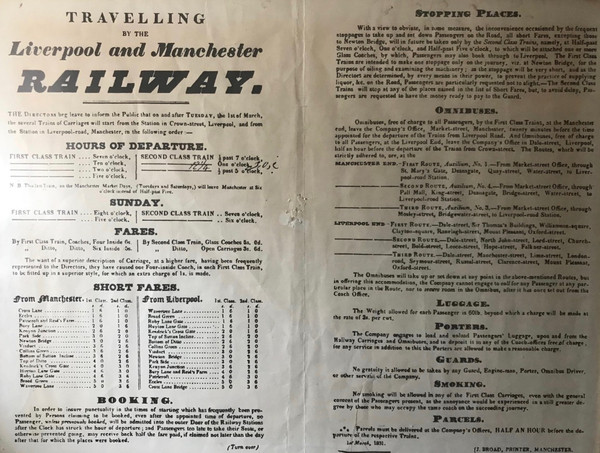

- Proper stations

- Scheduled services

- Double tracks so trains could go both ways

- Standard time (because you needed clocks to match up!)

- Regular, affordable passenger travel

It didn’t just change transport — it changed how people thought about time, distance, and work.

Later, the line got absorbed into bigger railway companies, but parts of it are still used today. Liverpool Road station in Manchester is now part of the Science and Industry Museum. If you’ve never been, go — it’s brilliant.

Growing up in Liverpool, I’ve always been a bit obsessed with this railway. You can still stand near Edge Hill or Lime Street and think about those early trains, belching steam and making history.

So that’s the story, at least my long-winded version of it.

Hope you enjoyed reading this.