George Stephenson (1781–1848) is widely recognised as one of the founding fathers of the railway age, and nowhere was his impact more profound than in Liverpool. Although he is often associated primarily with the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, Stephenson’s contributions to Liverpool’s railway history extended far beyond the establishment of a single line. His engineering vision, practical solutions to unprecedented challenges, and influence on later developments helped lay the foundations for Liverpool’s emergence as a major railway hub.

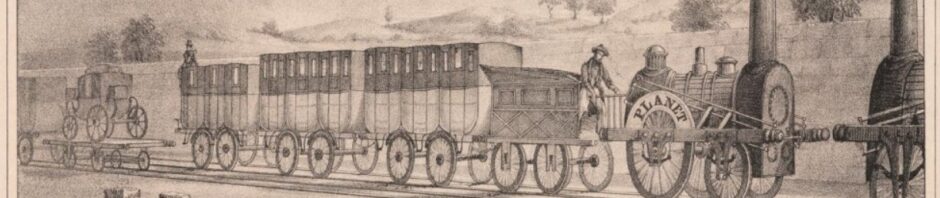

In 1824, Stephenson was appointed as the chief engineer for the proposed Liverpool and Manchester Railway. His task was formidable. The route had to navigate complex terrain, including the dense urban environment of Liverpool itself, and he had to convince many sceptical investors and landowners that steam locomotion was viable. His appointment was significant because it placed him at the centre of Liverpool’s early railway ambitions. The L&MR was approved by Parliament in 1826 after Stephenson addressed various technical objections during a series of exhaustive hearings. His practical experience working with steam engines and mining operations gave him a unique authority. Liverpool’s leading merchants, desperate for a faster, more reliable route to Manchester’s markets, placed their trust in Stephenson’s expertise.

One of Stephenson’s most remarkable achievements in Liverpool was the construction of the Wapping Tunnel. Completed between 1826 and 1829, it was the world’s first tunnel to be bored under a major city. Stretching approximately 2,250 yards (around 2km), the tunnel connected Edge Hill station with the Park Lane Goods Station at Liverpool’s docks. This tunnel was vital. It enabled goods to travel directly between the railway network and the bustling port of Liverpool without clogging up the city streets. The tunnel was dug through unstable sandstone and required innovative techniques for ventilation and drainage. Ventilation shafts, some of which still exist today, were strategically placed along its length. Interestingly, the Wapping Tunnel’s gradient was so steep (approximately 1 in 48) that it was initially worked using stationary steam engines and a cable haulage system. Trains would be attached to a continuous rope which was wound around a drum powered by the stationary engine. Stephenson’s cable haulage solution was a pragmatic response to the limitations of early locomotives, which were not powerful enough to haul heavy loads up such steep inclines unaided.

At Edge Hill, Stephenson established a key operational point for Liverpool’s railway system. The original Edge Hill station opened in 1830 and functioned as the technical heart of Liverpool’s rail operation. Trains were cable-hauled up from the Wapping Tunnel to Edge Hill using the stationary engines, and from there, locomotives could take over for onward journeys. This division of labour — stationary engines for steep urban sections, and locomotives for flatter countryside runs — was typical of Stephenson’s practical engineering philosophy. Rather than insist on one method of propulsion, he used whatever approach best suited the immediate problem.

Stephenson’s influence in Liverpool did not end with the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in September 1830. His work demonstrated that complex engineering problems could be overcome, encouraging further railway development in and around the city. Projects such as the expansion of Liverpool Lime Street Station (opened in 1836) and subsequent connections to other towns and cities built directly on the infrastructure and principles that Stephenson helped to establish. Moreover, Stephenson’s work helped to cement Liverpool’s reputation as a pioneering city in the railway age. Other cities took note of what had been accomplished in Liverpool, and the techniques and technologies pioneered under Stephenson’s guidance were adopted elsewhere.

George Stephenson statute outside the National Railway Museum. With thanks to Photo by and copyright Tagishsimon, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Another of Stephenson’s lasting impacts on Liverpool, and indeed on the national railway network, was his role in the adoption of standard gauge track. The 4 feet 8½ inches gauge he employed became the de facto standard for most of Britain’s railways. This standardisation made it possible for Liverpool’s network to connect seamlessly with new lines being built in the decades that followed. Stephenson’s insistence on durable construction, reliable engineering, and scalable systems ensured that Liverpool’s early railways could evolve as demand increased.

George Stephenson’s role in Liverpool’s railway history cannot be overstated. While the Liverpool and Manchester Railway often dominates the discussion, his wider contributions — particularly the Wapping Tunnel, Edge Hill station, and the practical establishment of standards — played a critical role in shaping Liverpool’s future as a railway city. His engineering solutions to the challenges of Liverpool’s urban environment demonstrated ingenuity and pragmatism, setting examples that would be followed across Britain and around the world. Without Stephenson’s vision and skill, Liverpool’s railway story might have been very different.